Target 3: creating a branch¶

With checkout command you learned to move from one commit

to another.

All you need is the key of the commit where you want to land

If you wanted to go on commit B you should type git checkout 2a17c43,

in order to go back to commit C you should use instead git checkout deaddd3

and so on.

But, we have to admit: managing commit A, B e C

having to call them 56674fb, 2a17c43 and deaddd3 is really

unconvinient.

git solves the problem doing what every judicious programmer would do: since those numbers are pointers to objects, git allows to use variables to store their values. Assigning a value to a variable is simple. If you correctly executed last checkout, you should be on commit C. Ok, now type:

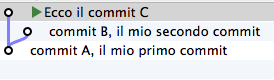

git branch bob 56674fb # here I'm using commit A's key

Can you see the bob label in correspondence of commit A?

It stays to indicate that bob points precisely that commit.

Look at it as it was a variable to which you have assigned the value of the commit A’s

key.

When you create a label, if you don’t specify a value, git will use the

key of the commit you are at the moment in

git checkout 300c737

git branch piccio

Removal of a variable is equally trivial:

git branch -d bob

git branch -d piccio

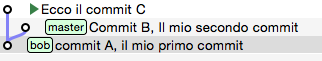

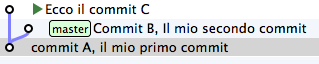

You may have noticed that git creates some of these variables by default. For

instance, in the above images you see also the master variable,

pointed to B

The master label allows you to go to that commit writing:

git checkout master

Now be careful, because we are again in one of those occasions where the

knowledge of SVN gives only headaches: these labels in git are named

branches. Repeat many times to yourself: in git a branch is not a

branch, it’s a label, a pointer to a commit, a variable that contains

the key of a commit. Many git’s behaviours that appear absurd and

complicated become very simple if you avoid thinking of git’s branches

as something equivalent to SVN’s branches.

It should now begin to be clear for you why many people say that “branches on git are very economical”: of course! they are simple variables!

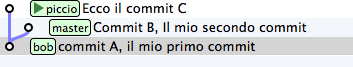

Create a new branch that we’ll use in next pages

git branch dev

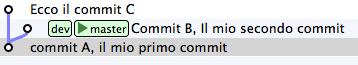

Note another thing: do you see that next to master SmartGit adds a

green triangle placeholder? That symbol indicates that in this moment

you are attached to the master branch , because your latter

moving command was git checkout master.

You might move on dev with

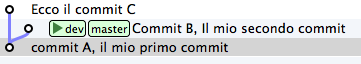

git checkout dev

Have you seen? The placeholder has moved on dev.

That placeholder’s name is HEAD. By default, in fact, git always

adds also an implicit branch , the HEAD pointer, always pointing

to the element of the repository where you are. HEAD follows

you, any movement you do. Other graphical editors use different

representations to communicate where HEAD is.

gitk, for instance, shows in bold the branch where you are. Instead,

from the command line, to know on which branch you are, you just type

git branch

* dev

master

The star suggests that HEAD is now pointing to dev.

You should be not that much surprised veryfing that, despite you’ve

changed branch from master to dev, your file system has

not changed one iota: in effect both dev and master are

pointing to the same identical commit.

Nevertheless, you’ll might wonder what can serve passing from one branch

to another, if it doesn’t produce effects on the project.

The fact is that when you run the checkout of a branch, you somehow

attach to the branch; the branch’s label, in

other words, will start following you, commit after commit.

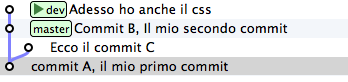

Look: you are now on dev. Make some modifications and commit

touch style.css

git add style.css

git commit -m "Now I have also css"

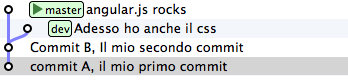

Have you seen what has happened? The label dev has moved onward and

attached to your new commit.

You might also wonder why git calls those labels branches.

The reason is that, even though diverging development lines in git are

not branches, branches are normally used just to give them a name.

Look at it in concrete. Go back to master and make some change.

git checkout master

touch angular.js

git add angular.js

git commit -m "angular.js rocks"

As you could expect, the master label has moved one place onward, and

points to your new commit.

Now there’s a certain equality between development lines and branches.

Despite this, you’ll want to keep always mentally separate the two concepts,

because this will make much easier the management of the history of your

project.

For instance: no doubt is commit with comment “angular.js

rocks” contained in branch master, isn’t it? But what about

A and B? Which branch do they belong to?

Pay attention, because this is another of those concepts that cause headache to SVN’s users, even to Mercurial’s ones.

In effect, in order to answer this question, git’s users make a different question:

“is ``commit A`` reachable from ``master``?”

That is: if we walk backwards the history of commit starting from

master, do we pass by A? If the answer is yes we can state that

master contains the changes introduced by A.

One thing that Mercurial’s and SVN’s fans might find misleading is that,

since commit A is reachable also from dev , it belongs both to

master and to dev.

Think it over. If you treat branches like pointers to commit everything

should appear very linear to you.