Target 6: placing the repository on the network¶

So far you have interacted only with your local repository , but I had

anticipated that git is a peer-to-peer system.

In general, this means that your repository is a node that can

become part of a network and exchange information with other nodes,

that is, with other repositories.

A part from your local repository, any other repository

–no matter if it’s on GitHub, on a company’s server or simply in a different

directory of your computer– for git it’s a

remote.

To link your local repository to a remote you just need to

give git the address of the remote repository with the command

git remote (of course, you need also read and write permissions on remote)

To make things simple, let’s make a concrete example without

involving external servers and the Internet; create another repository

somewhere on your very computer

cd ..

mkdir remote-repo

cd remote-repo

git init

In this case, in the directory of your project, the remote repository

will be reachable through the path ../remote-repo or with its absolute path.

But, more commonly, you wil deal with remote repositories that are reachable, depending on

the protocol that is used, with addresses like

https://azienda.com/repositories/cool-project2.gitgit@github.com:johncarpenter/mytool.git.

For instance, the repository of this guide has the address

git@github.com:arialdomartini/get-git-english.git.

It also happens very often that accessing to a remote requires an

authentication. In this case, usually, it’s used a user/password pair

or a ssh key.

Go back to your project

cd ../project

Well. Add to the remote list the repository just created,

indicating to git whatever name and the address of remote

git remote add foobar ../remote-repo

Very good. You have linked your repository to another node. You are

officially in a peer-to-peer network of repositories. From this moment,

when you want to make reference to that remote repository, you will use

the name foobar.

Name is necessary, because, differently from SVN that has the concept of

central server, in git you may be linked to whatever number of remote

repositories at the same time, therefore you will assign a unique identifier to each of them.

There are two things that you fundamentally may do with a remote:

to align with its content or to ask it for aligning with you.

Two commands are available: push and fetch.

With push you can deliver a set of commits to the remote repository.

With fetch you can receive them from the remote repository.

Both push and fetch, actually, allow that your repository

and the remote exchange labels. And, indeed, you have also other commands

available. But let’s go step by step: let’s start to see in concrete how

the communication between a repository``and a ``remote works.

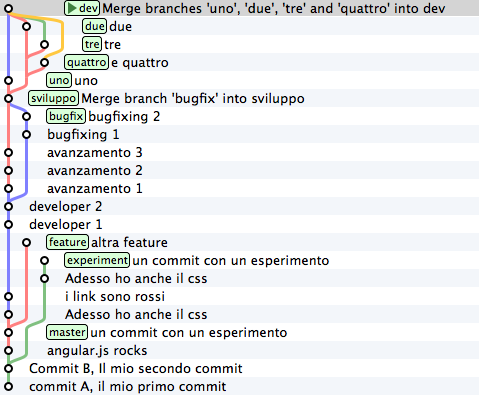

Delivering a branch with push¶

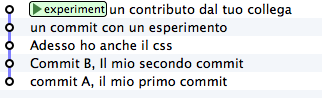

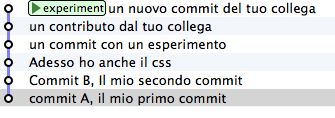

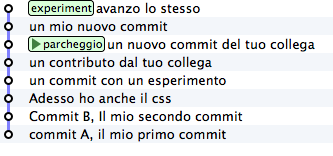

At the moment the remote that you named foobar is a completely empty repository:

you just created it. Your local repository , instead, contains many

commits and many branches:

Try to ask the remote repository for giving you the commits and the

branches which it has available and which you don’t have. If you don’t indicate a

specific branch , the remote repository will try to give you all of them.

In your case the remote is empty, therefore it shouldn’t give anything back to you

git fetch foobar

In fact. You don’t receive anything.

Try instead to deliver the branch

experiment

git push foobar experiment

Counting objects: 14, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (8/8), done.

Writing objects: 100% (14/14), 1.07 KiB \| 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 14 (delta 3), reused 0 (delta 0) To ../remote-repo

[new branch] experiment -> experiment

Wow! Something happened! Among all the response messages, at this moment the most interesting is the last one

[new branch] experiment -> experiment

I help you to interpret what has happened:

- with

git push foobar experimentyou asked git for sendingfoobartheexperimentbranch - to execute the command git took into consideration your

branchexperimentand drew the list of allcommitsreachable from that branch (as a usual: they are all thecommitswhich you may find starting fromexperimentand following backward in time any path you may go through) - git has then contacted the remote

repositoryfoobarto know which of thosecommitswere not present remotely - after that, it created a packet with all the necessary

commits, delivered them and asked the remoterepositoryfor adding them to its own database - the

remotehas placed itsbranchexperimentso that it pointed exactly the samecommitpointed on your localrepository. Theremotedidn’t have thatbranch, therefore it created it.

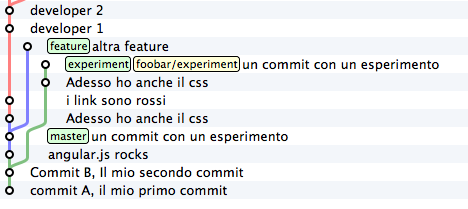

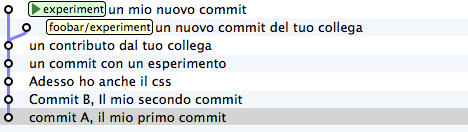

Now try to visualize the remote repository

Do you see? The remote has not become a copy of your repository:

it contains only the branch that you sent it.

You may verify that the 4 commits really are all and only the

commits that you had in local on the experiment branch.

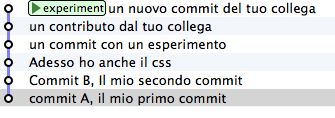

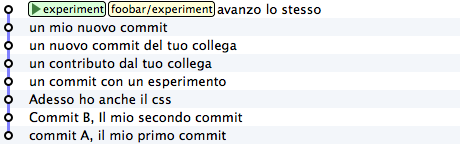

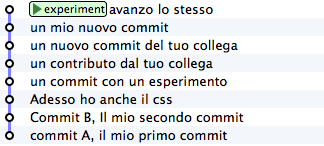

Even on your local repository something happened. Try to visualize it

Look, look! It seems that a new branch, called

foobar/experiment, has been added. And it also seems that it’s a little particular

branch, because the interface draws it in a different colour.

Try to delete that branch

git branch -d foobar/experiment

error: branch 'foobar/experiment' not found.

It cannot be deleted. git says that branch doesn’t exist. Uhm.

That label has really something particular!

The fact is that branch is not on your repository: it’s on

foobar. git has added a remote branch in order to allow you to

keep track of the fact that on foobar the branch experiment

is just pointing to that commit.

remote branches are a sort of reminder that allow you to understand

where branches are on remote repositories you are linked with.

It’s one of those subjects that may result less clear to new git users,

but if you think of it, the concept is not difficult at all. With the

remote branch called foobar/experiment git is simply telling you

that the branch experiment on the foobar repository is

in correspondence of that commit.

As well as you can’t delete that branch you can not even move it directly.

The only manner to gain direct control on that branch``is to access directly

the ``foobar repository.

But you have an indirect way to control, delivering with push an update of

experiment branch; we had seen before that the``push`` request is always

accompanied by the request of update of the position of your branch.

Before trying with a concrete example, I’d like to draw your attention on

a very important aspect, that you will have to get used to: while you were

reading these lines, a colleague of yours could have added some commit

just on his branch experiment on his remote repository, and

you wouldn’t know anything, because your repository is not linked in

real time with its remotes, but synchronizes only when you interact with

proper commands. Therefore, the commit pointed by foobar/experiment

has to be meant as the last known position of the experiment branch

on foobar.

Receiving updates with fetch¶

Let’s try and simulate this last case.

Change foobar as if a colleague of yours is working on experiment.

That is: add a commit on the experiment branch of foobar

cd ../remote-repo

touch x

git add x

git commit -m "a contribution from your colleague"

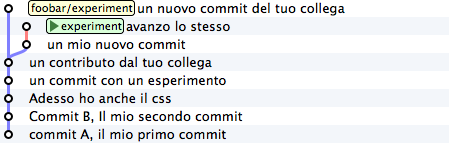

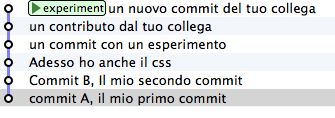

Here you have the final result on foobar

Go back to your local``repository`` and let’s see what has changed

cd ../project

In fact. It has not changed anything at all. Your local``repository``

continues to say that the experiment branch on foobar stays at

“a commit with an experiment”. And you know very well that it’s not true!

foobar has gone forward, and your repository doesn’t know it.

All this is coherent with what I said before: your

repository is not linked in real time with its remote; matching

is only on command.

Then ask your repository for matching with foobar. You

may ask for an update on a single branch or on all of them.

Usually it’s chosen the second way.

git fetch foobar

remote: Counting objects: 3, done. remote:

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done. remote: Total 2 (delta 1),

reused 0 (delta 0) Unpacking objects: 100% (2/2), done.

From ../remote-repo

e5bb7c4..c8528bb experiment -> foobar/experiment

Something has arrived.

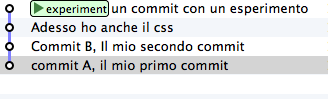

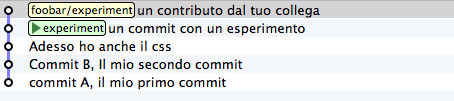

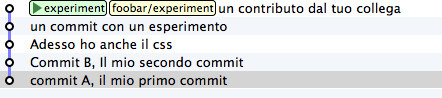

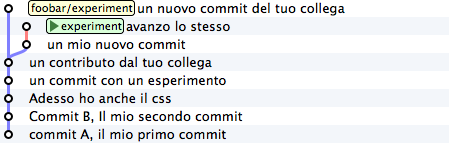

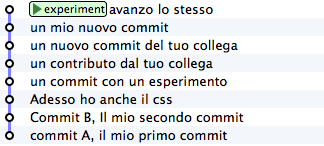

Look again at the new local repository. (In order to simplify our life,

let’s start to take advantage from an option present in every git’s graphic

interface: the capability of visualizing a single branch and of hiding all

others, so that final result can be simplified)

Carefully look at what has happened: your experiment branch

didn’t move at all. If you check, your

file system hasn’t absolutely changed either. Just your local

repository has been updated: git added there a new

commit, the same added remotely; at the same time, git has also

updated the foobar/experiment position, in order to communicate

that “according with latest available information, last position of

the branch ``experiment`` recorded on ``foobar`` is this”.

This is the way with which git normally allows you to know that

someone continued his work on a remote repository .

Another important remark: fetch is not equivalent to

svn update; only your local repository is synced to

the remote one; your file system has not changed! This generally means that

fetch is a very safe operation: even though you should sync

with a dubious quality repository, you can rest easy,

because the operation will never apply the

merge on your code without your explicit intervention.

If instead you really want to include the remotely introduced changes in

your work, you could use the merge command.

git merge foobar/experiment

Do you recognize the kind of merge that resulted? Yes, a

fast-forward. Interpret it this way: your merge has been a

fast-forward because while your colleague was working, the branch

has not been modified by anyone else; your colleague has been the only one

who added contributions, and development has been linear.

This is such a common case that you will want to avoid doing

git fetch followed by git merge: git offers the

git pull command, which executes the two commands together.

Therefore, instead of

git fetch foobar

git merge foobar/experiment

you should have run

git pull foobar experiment

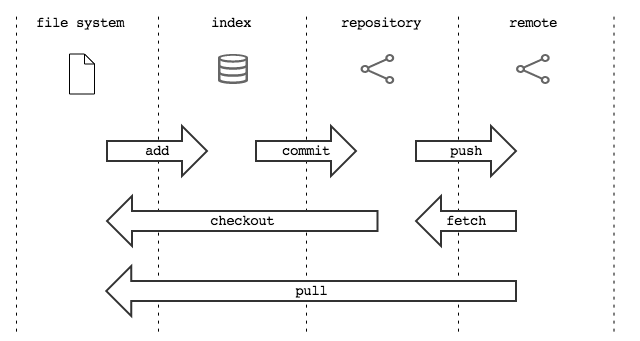

We can extend the diagram of te interactions between git commands and

its environments adding the remote column and the action of

push, fetch e pull

Non linear development¶

Let’s try to complicate the situation. I would like to show a case that

will continously happen: two developers are working on a branch at the same time,

on two separated repositories . It usually happens that at the moment when you

will want to send your new commits to remote , you discover that,

in the meantime, someone on the remote

repository changed the``branch``.

Start to simulate your colleague’s work progress, adding

a commit on its repository

cd ../remote-repo

touch progress && git add progress

git commit -m "a new commit of your colleague"

(En passant, note this: on the remote repository there’s no indication

of your repository; git is an asymmetric peer-to-peer system)

Go back to your repository

Like before: as soon as you don’t explicitly ask for an alignment with

fetch, your repository doesn’t know anything of your new commit.

By the way, this is one of remarkable git’s features: being

compatible with the strongly non linear nature of development activities.

Think it over: when two developers work on a single branch,

SVN requires that every commit is preceded by an update; that is,

in order to record a change the developer has to integrate preventively the

other developer’s work. You cannot run a

commit if you beforehand don’t integrate your colleague’s commits .

git, on this viewpoint, is less demanding: developers may diverge locally,

even working on the same branch; the decision if and how to integrate their work

may be intentionally and indefinitely moved on in time.

Anyway: embrace the strongly non linear git’s nature and, purposely ignoring that there

could have been progresses on the remote repository , proceed locally without delay

with your new commits

cd ../project

touch my-contribution && git add my-contribution

git commit -m "a new commit of mine"

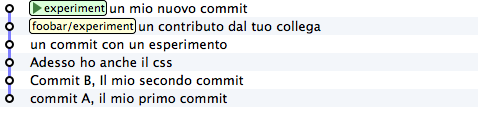

Let’s assess again the situation concerning what I have just described:

- your

repositorydoesn’t know about the newcommitrecorded onfoobarand continues to see a not up to date situation - starting with the same

commit“a contribution from your colleague” you and the other developer have recorded two completely indipendentcommits.

Having worked concurrently on the same branch, with two potentially incompatible commits,

if you think of it, is a little like working concurrently on the same file with potentially incompatible changes:

when the two results will be put together, we can expect that a conflict is reported.

And infact it’s just like this. The confict arises at the moment when

we try to sync the two repositories. For example: try to send

your branch on foobar

git push foobar experiment

To ../repo-remoto ! [rejected]

experiment -> experiment (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to '../repo-remoto'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do

hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing

hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes

hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.

Rejected. Failed. Error. It’s more than evident that the operation has not

been successful. And we could expect it. With

git push foobar experiment you had asked foobar for completing two operations:

- saving in its database all yours

commitsthat are not yet remotely present - moving its

experimentlabel so that it points the same``commit`` that is pointed locally

Now: about first operation there would have been no problem.

But, about the second one, git sets a supplemental costraint:

the remote repository will move its label only on condition that the

operation can be completed with a fast-forward, that is, only on

condition that it’s not necessary to execute merges.

Or, said in different word: a remote accepts a branch

only if the operation doesn’t create diverging development lines.

fast-forward is mentioned just on the last line of the error message

hint: **See the 'Note about fast-forwards'** in 'git push --help'

for details.<br/

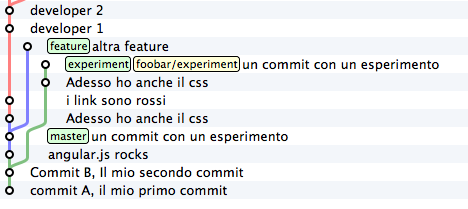

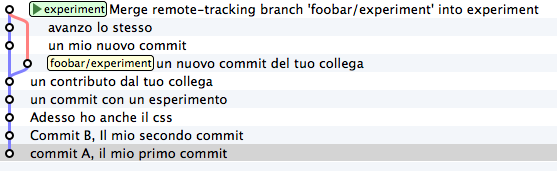

In the same message git provides a tip: it suggests to try to fetch. Let’s try

git fetch foobar

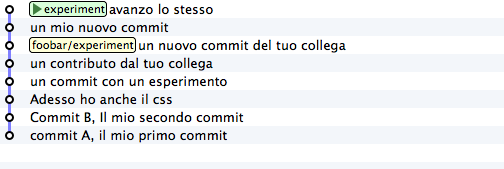

The situation should be clear at a glance. You can see that the two development lines are diverging.

The position of the two branches helps in understanding where you are locally and where your colleague is

on the remote foobar.

We have just to decide what to do. Unlike SVN, that in front of this situatuon would have necessarily required a local merge, git leaves to you three possibilities

- going on ignoring the colleague: you may ignore your colleague’s

- work and continue on your development line; of course, you will not

be able to deliver you branch on

foobar, because it’s incompatible with your colleague’s work (even though you may deliver your work assigning to your development line another name, creating a newbranchandpushingit); however, the concept is that you’re not obliged to integrate your colleague’s work;

- ``merge``: you may melt your work with your colleague’s one with a

merge - ``rebase``you may realign to your colleague’s work with a

rebase

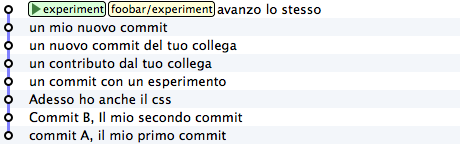

Try the third of these possibilities. Nay, in order to insist on the non linear nature of git, try to make the first way precede the third. In other words, try to see what happens if, temporarily, you ignore the misalignment with your colleague’s work and you keep on developing on your line. It’s a very common case: You know you have to align, sooner or later, with the others’ work, but you want to complete your work, beforehand. git doesn’t dictate timing and doesn’t oblige you to anticipate things you don’t want to do anon.

echo change >> my-contribution

git commit -am "I progress the same"

Very well. You went on with your work, misaligning even more with your colleague’s

work. Let’s suppose that you decide the moment has arrived for realigning, and then

delivering your work to foobar.

You might run git merge foobar/experiment and obtain this situation

Do you see? Now foobar/experiment could be pushed forward (with

a fast-forward) till experiment. Then, you could run git push foobar.

But instead of doing a merge, do something more sophisticated: use

rebase. Look again at current situation

.. figure:: img/collaborating-3.png

With respect to the works on foobar it’s as if you had detached a development branch

but, unfortunately, while you were making changes,

foobar has not waited for you and has been modified.

Well: if you remember, rebase allows you to apply all your changes to another

commit; you could apply your branch to foobar/experiment. It’s like if you could sharply

detach your branch experiment and reattach on another base

(foobar/experiment)

Try

git rebase foobar/experiment

Have you seen? To all effects it appears as if you had started your work

after the end of works on foobar. In other words:

rebase has apparently made linear the development process, that was

inherently non linear, without forcing you to align with your colleague’s work

exactly in the moments when it was adding

commits to its repository.

You may deliver your work to foobar: it will appear how you have made your changes

starting with the last commit done on

foobar.

**git push foobar experiment**\

Counting objects: 6, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (4/4), done.

Writing objects: 100% (5/5), 510 bytes \| 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 5 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: error: refusing to update checked out branch: refs/heads/experiment

remote: error: By default, updating the current branch in a non-bare repository

remote: error: is denied, because it will make the index and work

tree >inconsistent

remote: error: with what you pushed, and will require 'git reset --hard' to match

remote: error: the work tree to HEAD.

remote: error: remote: error: You can set 'receive.denyCurrentBranch' configuration variable to

remote: error: 'ignore' or 'warn' in the remote repository to allow pushing into

remote: error: its current branch; however, this is not recommended unless you

remote: error: arranged to update its work tree to match what you pushed in some remote: error: other way.

remote: error:

remote: error: To squelch this message and still keep the default behaviour, set

remote: error: 'receive.denyCurrentBranch' configuration variable to 'refuse'.

To ../repo-remoto ! [remote rejected] experiment -> experiment (branch is currently checked out)

error: failed to push some refs to '../repo-remoto'

My God! It really looks like git didn’t like this push .

In the very long error message git is saying that it may not

push a branch currently “checked out”:

the problem doesn’t seem to be in``push`` itself, but in the fact

that on the other repository your colleague did checkout experiment.

This issue could continously happen, if you don’t know how to face it,

therefore we will soon dedicate a little time to it. For now,

repair gently asking your colleague for moving on another branch and repeat push.

Then: on foobar move on another branch

cd ../remote-repo

git checkout -b parking

And afterwards, go back to your local repository and repeat push

cd ../project

git push foobar experiment

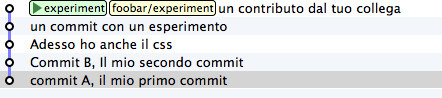

Here you have the result

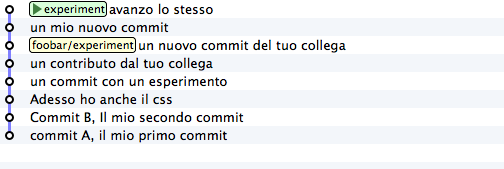

Let’s run graphically through what has happened. You were leaving from

Then you run rebase and you obtained

Then you run push on foobar: the new position of the

remote branch foobar/experiment is witnessing the progress of the branch

also on the remote repository .

Simultaneously, your colleague on foobar saw its repository

passing from

to

Can you get everything? Look carefully at the last two images, because

it’s just in order to avoid what you are seeing that git complained that much,

when you run git push foobar experiment.

In order to understand it, put yourself in the shoes of your virtual colleague,

that we imagined on the remote repository foobar. Your colleagues is

staying quiet on the experiment branch

when suddenly , without he gave any command to git, his

repository accepts the request of push, stores in the local database

a couple of new``commits`` and moves the experiment branch (yes,

just the branch of which he run the checkout!) two commits forward

You will admit that if this was the standard behaviour of git,

you would never find yourself in your virtual colleague’s position:

loss of control of your repository and of your

file system would be too high a price to be paid.

You well understand that changing the branch where you run checkout

substantially means seeing your

file system change under your feet. Of course this is totally unacceptable,

and for this reason git refused proceeding and replied with a lengthy error message.

Before you remedied the situation moving your virtual colleague on a parking branch,

just for being able to send it your branch.

This dirty trick allowed you to push experiment.

But, thinking about it, this is as well a solution you probably will never accept:

aside from the convenience of having to suspend just because a colleague wants to deliver his code,

however you wouldn’t like that the progress of your branches is

completely out of your control, at the mercy of anyone. Because, in the end

the experiment branch would move forward against your will, and it could happen the same

to all the branches that you did not checkout.

It’s evident that a radical solution to this problem must exist.

The solution is amazingly simple: you don’t allow others to access your ``repository``.

You might find it a somewhat cursory solution, but you should recognize that a more drastic and effective system doesn’t exist. And, fortunately, it’s much less limiting than you could expect at a first analysis.

Of course I told you only half of the story and maybe it’s worth to deepen a little the matter. Open very well your mind, because now you are getting to the heart of a very fascinating subject: git’s distributed nature. It’s likely to be the most commonly unappreciated aspect of git and, nearly certainly, one of its most powerful features.